Serious mistakes by hospital staff that put patients at risk are on the rise, despite the government’s drive since the Mid Staffs scandal to make care safer, official NHS figures reveal.

The last few years have seen more cases of delayed diagnosis, staff failure to act on patients’ test results, poor care of seriously ill patients and blunders during surgery.

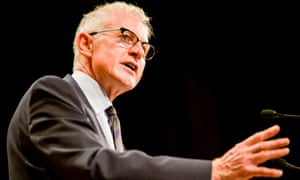

The figures, obtained by former health minister Norman Lamb from NHS England, have sparked concern that the unprecedented strain on hospitals – created by rising demand for care, shortages of doctors and nurses, and the need to save money – is making staff more likely to make errors.

The number of cases in which NHS England recorded that a patient whose health was deteriorating received what it calls sub-optimal care more than doubled, from 260 in 2013-14 to 588 in 2015-16. Similarly, the number of diagnostic incidents – either a delayed diagnosis or an NHS worker not acting on test results – rose from 654 to 923.

“Jeremy Hunt [the health secretary] has talked a lot about wanting to make the NHS the safest healthcare system in the world,” said Lamb. “But is that ambition realistic? These figures show worrying rises in the number of incidents which have a damaging and potentially fatal effect on patients.

“My worry is that the NHS is under such impossible pressure, with clinicians too often working under intense strain, that increases the risk of serious harm being caused to patients, which can have incalculable consequences for them and their families.

“These figures confirm the stark and distressing reality that thousands of people are being failed in their hour of need because the NHS is under such intolerable pressure, with overstretched hospital staff unable to give patients the care and treatment they deserve,” he added.

The figures that he obtained, using the Freedom of Information Act, also show that the number of surgical incidents more than doubled from 285 in 2013-14 to 740 in 2015-16. There were 202 surgical errors and 83 cases of wrong-site surgery – in which surgeons operated on the wrong part of a patient’s body – during 2013-14. They rose to 248 and 114 respectively a year later.

But after changing the way it collates data in May 2015 regarding incidents in which patient safety is endangered, NHS England says that 30 surgical errors and 19 wrong-site surgeries occurred in 2015-16, as did another 691 cases of a “surgical/invasive procedure incident”.

The disclosures come amid growing fears among NHS bodies, health trade unions and thinktanks that the service in England will experience its first full-blown winter crisis since 2011-12 and that both the quality and safety of care are in danger of deteriorating in coming weeks and months.

Worsening gaps in medical rotas, big year-on-year rises in the number of patients attending and being admitted, and the growing complexity of patients’ illnesses are also key factors.

Hunt has launched an array of initiatives to improve the safety of NHS care since Robert Francis QC’s seminal report in 2013 into the scandal of poor care at Stafford Hospital between 2005 and 2009, which led to patients dying.

“We have long warned that underfunding and staff shortages within the NHS will impact on patient safety. It appears that our worst fears are now being confirmed,” said Eddie Saville, general secretary of the Hospital Consultants and Specialists Association, which represents several thousand hospital doctors.

“Hospital doctors and fellow medical staff are increasingly hampered by the spending constraints placed on frontline services. It is time that the government listened to those voices warning that it has got funding wrong. It shouldn’t be a case of waiting for a major incident to hit the headlines before acknowledging this fact and changing tack.”

The figures also paint a mixed picture of patient safety in NHS maternity services. There were fewer maternity-service serious incidents (82), mothers’ unplanned admissions to intensive care (134) and unexpected neonatal deaths of a newborn (122) in 2014-15, compared with 2013-14. However, 535 newborn babies had to be admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit in 2014-15, up from 380 the year before. The number of maternal deaths also rose over the same period from 54 to 62.

The Department of Health denied the figures were proof that patient safety was slipping. “To suggest this indicates a decline in standards is a simple misreading of the information,” a spokesman insisted. The rises in these types of serious breaches of safety were due to better recording of such occurrences, he said.

“This data is precisely what we would expect given the government’s focus on building the safest and most transparent healthcare system in the world. The NHS is becoming far better at recording and learning from the open reporting of a wider range of incidents,” he said.

Serious mistakes in NHS patient care are on the rise, figures reveal