Beauty has seizures, and she worries about what she’ll be doing when the next one occurs. She was lucky with the first: she was in bed asleep next to her boyfriend, who woke to the bed shaking and was quick to pry his 24-year-old girlfriend’s jaw open to prevent her from biting her tongue. Since then she’s fallen down in the street and ended up alone in the hospital ICU, and so she lives in fear.

She thought she was doing the right thing by sticking with K2, her drug of choice.

In the South Bronx, a community known to struggle with addiction, Beauty chooses an active rebellion from the norm: she refuses to use crack, which removed her mother from her childhood, as well as heroin, which she’s seen turn functioning people into perpetually sick ones. Beauty’s drug, by contrast, is legally sold in corner stores. It couldn’t be so bad, she thought.

While she is neither dealt daily nausea from withdrawal (as with heroin users), nor risking arrest for drug paraphernalia (as with crack users), she is the only one in her peer group who seizes, and the only one whose drug produces a range of widely differing and often unknown effects. The drawbacks from crack and heroin – even a “speedball” mixture of the two – can be anticipated, but smoking K2 is a gamble.

The packages she favors seem child-sized, smaller than Ziploc sandwich bags. They’re adorned with swirls of pink, purple and green surrounding a cartoon Scooby-Doo, tongue out the side of his mouth. The words “Scooby Snax Potpourri” headline the bag containing what the media refers to as “synthetic marijuana”.

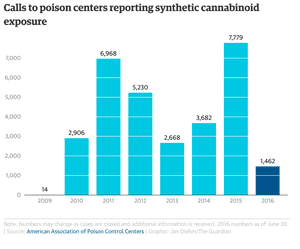

However familiar and innocuous the reference to marijuana makes the drug sound, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a 229% increase in calls to US poison centers due to K2 or Spice (street names for synthetic cannabinoid mixes) between January and May 2015.

Major cities, too, have noticed a rise in use. In September 2015, New York City’s mayor, Bill de Blasio, announced a partnership with the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) to target both demand and supply-side factors as well as distribution in the area (earlier this month, 33 people reported extreme adverse reactions to the drug in Brooklyn). On an international level, in 2012 the DEA launched a project to combat the spread of K2 and other synthetic drugs like it.

Beauty buys a pack of her choice K2 brand for $ 10 from a corner store in the Bronx, as nonchalantly as she would buy a pack of cigarettes. She may get arrested for possessing marijuana and harder drugs, but not for this.

In her early days on the streets, pre-K2, she was lithe, with thick, winged eyeliner and electric tights. Her presence, cheerful, bounding, wild in gesture and loud in volume, was both innocent and magnetic, drawing her easy friendships. Her stance away from hard drugs made her alluring to those who had been in the neighborhood a while. Everyone presumed this stance was a show, but over time it became apparent that it was simply truth.

On this point, she was stubborn and relentless. She would be different; she would not get stuck out on the street for years. She would make a functional life, starting with her dream of finding real, lasting love with a decent man.

“I just wanna find somebody that will respect me and won’t play, then move somewhere nice … find a little house,” she said. Until then, “I’m gonna do what I have to do” to make a living: walk the streets.

Within a week or so of her arrival in the Bronx, Beauty found who she hoped would be a boyfriend fitting her ideal. Amid quick declarations of love, this man quickly gave her a place to stay, took charge of the money she made selling her body, some of which he portioned out for Beauty to spend on new clothes, shoes and a cellphone – a role insinuating “pimp” in everything but name. He also provided a guise of protection against ill-intentioned johns when Beauty climbed into unknown cars and spent his days tracking her movements.

At the same time, he introduced her to K2, buying her packs for encouragement and good behavior.

Perhaps this introduction was well-intended or benign, perhaps not; Beauty’s later boyfriends did little to discourage her drug habit. Under its influence, she was a bit less wild, less prone to yell obscenities in the street when frustrated, and more controllable.

Beauty believes she made a hard-learned, measured decision in her adoption of K2 as drug of choice, one she stands by even still. No one forced her: she tried it and liked how it made her feel.

Friends who use crack and heroin, however, are suspicious of her drug and refuse to partake in it.

“I tried that stuff once, and I could only turn left,” Prince, a 37-year-old heroin user said, miming a fast stride in a tight circle. “No way I’m doing that again. That’ll mess you up.”

The contents of K2 baggies, after tearing away the plastic seal, look something akin to marijuana: clumps of earthy green that are laid inside rolling papers to smoke.

The resemblance to marijuana stops with the nickname and appearance: though K2 and marijuana both interact with cannabinoid receptors in the central nervous system to produce psychoactive effects, they do so differently, with the lab-bred synthetics binding and activating receptors to potentially detrimental degrees for people who ingest them. Along with this, synthetics repeatedly change, with batches containing widely differing substances at differing concentrations.

To manufacture K2, varying chemical combinations of unknown potency are often purchased from China, imported to the US, then dissolved in acetone to be poured or sprayed over plant material before packaging. The mixing process is notoriously inconsistent, known to involve implements as varied as industrial cement mixers to bathtubs. Alternatively, the entire mixture may be purchased wholesale from international sellers, both methods potentially cutting six-figure profits for distributors, according to Rusty Payne, public affairs officer for the DEA.

Packs of K2 are then sold with no hint at their chemical contents or the variation lying within, instead just simply emblazoned with directives such as “for aromatherapy use only”, “not for human consumption” or “incense”.

Known effects of ingesting the combinations within the packs range from irritability to tachycardia and vomiting, to psychosis, even death, or seizures, as in Beauty’s case.

Yet however dangerous the drugs may be, the seemingly rational efforts to control them are actually part of the problem.

Packages of K2 exist in a public health grey space, neither controlled nor completely illegal, and outlawing them outright is complex if not impossible with current methods. Because the cannabinoid class of drugs is so broad and diverse, encompassing everything from medically prescribed marijuana to varieties of K2, one law cannot realistically ban the group altogether, and so to effectively target the K2 variants that have proven to be dangerous, lawmakers must ban by specific drug name once the substances have been established to be toxic.

The Synthetic Drug Control Act of 2015 contains a 28-page laundry list of more than 300 Schedule 1 substances – substances that are illegal in all settings and have high potential for abuse – to be added to the list of federally controlled substances.

Of this list, a hundred or so are synthetic cannabinoids written in chemist’s hand – thus, one hundred or so are substances that once rendered illegal will force K2 manufacturers to change the chemical ingredients for products currently on the market, 100 existing variants of an ever-increasing number barred.

Once a substance is outlawed and components of K2 packages tweaked, scientists must restart their process of uncovering how the drugs people buy affect their health because on a biological level – an altered substance is a brand new one with a new set of potential interactions and effects on the body.

Such regulatory changes create a cycle of scientists ever-testing new combinations of substance profiles, never given enough time to study and identify how existing drugs affect people before drug creators change the game by inserting novel substance structures.

It brings to mind the Greek myth of Hydra: each time legislation is passed to ban a substance, new unknown substances arise to take its place, which yields more potential chemical combinations in K2 packages.

Eventually the heads, the substance combinations and their toxicological effects, become innumerable, lessening the likelihood of scientists getting a handle on understanding how the drugs work in real-world human systems due to the sheer volume of potential combinations residing in packages sold.

Beauty has probably tried several (at minimum) compound combinations in her relationship with the drug but she will never be informed of it, as the packages and labels do not change when their contents do.

A sample of Beauty’s favored K2 purchased alongside her in Bronx, upon analysis by Kevin Shanks, a forensic toxicologist with AIT Laboratories in Indianapolis who specializes in the analytical detection and forensic toxicology of new psychoactive substances and other designer drugs, revealed six different synthetic cannabinoid compounds – some of which have been made illegal, some of which have not, each of which is likely interact with the body differently, made worse by dosages that vary between packages.

Payne, from a DEA perspective, likens the differentiation within and between packs to roulette.

“There are thousands and thousands of drug labs in China and elsewhere, and none of them – the labs, the distributors, the corner stores – care about the effects. All they want is your money,” Payne said. “This stuff is dangerous.”

Since some of the substances found in Beauty’s K2 sample (see analysis photos above) were added to the Schedule 1 Substance list in 2013 and 2014, the chemical composition in packs sold will probably be intentionally tweaked soon if it hasn’t been already. These are changes Beauty would fail to realize upon routine purchase of her favorite brand.

“What used to take years to synthesize now takes months or weeks,” said Payne.

Along with corner stores, the stuff can also be bought online, from websites proclaiming “legal herbal bud”. While the product description includes a “not for human consumption” disclaimer, it also boasts five-star customer reviews of people rolling up “100% Legal Herbal Spice”.

Beauty usually smokes along a cement foundation below a chain-link fence that buttresses a sports field. She smokes one joint after another, as much as she can in a day between turns in cars, as many as her boyfriend allows, which can be up to four packs. Four packs of compound cocktails, which she says she needs. Sometimes she has seizures; sometimes she doesn’t.

Lack of knowledge regarding the toxicological effects and biological interactions of K2 compound combinations make the mechanism for addiction and user dependency equally hard to uncover and explain.

Despite this, patient symptoms have arisen and persist since the drug’s advent in the early 2000s. Along with professed need akin to Beauty’s, clinicians have noted patient symptoms of increased heart rate and blood pressure, nausea, headaches and tremors indicative of withdrawal after K2 products have been ingested in large quantities.

This level of dependency, while presumably universally unappealing, was the last thing Beauty wanted – she had set out into her adult life in active defiance of such effects.

But the drug has a way to attract the young: whether it be through the lure of a more intense high than marijuana, the affordability and legal ease of obtaining it, or ancillary benefits – such as not appearing in typical employer-mandated drug testing. Combined, these spin an ill-fated illusion of a drug that isn’t so threatening.

User profiles place male adolescents to be at increased risk (young females to a lesser extent), with 11% of high school seniors shown in survey data conducted by Johns Hopkins University researchers to have tried synthetic cannabinoids like K2.

According to a review in Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry journal, those who use synthetic cannabinoids can be grouped into three main categories: “1) marijuana smokers, 2) occasional drug users seeking to avoid legal complications, and 3) drug-naive, curious experimenters.”

Beauty came to K2 with youthful naivety, alongside an intimate knowledge of what legal trouble with drugs entails, and by moving to a new place, the Bronx, she believed she abandoned the cyclical drug-related tensions that collected in her past back in Oklahoma, where she was born in prison to a woman who has since been incarcerated for crack cocaine possession over and over again.

On K2, Beauty often appears sleepy and faded, eyes heavily lidded, her body and mind hunched, effects among others that led news reports to refer to “zombies”. Sometimes she cannot speak, react when her name is called or recognize familiar faces so slowed are her responses under its influence.

Beauty says she smokes to lessen “anger issues” and relies more on K2 when she’s stressed, when she worries that she and her boyfriend won’t be placed in the same homeless shelter, or that he may leave her for another girl.

“I need it to chill me out, to just be cool around all this,” she said, gesturing at people around her, at the others who spend their days loitering around the concrete fence, people from the shelter across the street and men she’s dated.

In jail, where she occasionally lands for prostitution and drug possession (illegal drugs that she’s bought for male clients), she doesn’t need K2. The anger and rage against her environment that she spoke of, which once escalated to her kicking out a police van window, is assuaged by medications given to her in jail, ones tailored to mental illness that make her feel better. On these, she is able to do a job working in the kitchen, a job she’s skilled at and enjoys.

Upon her last release from Rikers Island jail, a six-month stint, she tried to prioritize other things: seeing people for the first time since her arrest, getting something to eat aside from jail-mandated options, before buying K2, but the plan fell apart the nearer to her usual store she went. K2 was first, smoked outside the door, rolled beneath the awning with her paperwork and possessions from jail in her arms.

Living out of jail, and away from K2, she has withdrawals, urgent psychological or physical needs for the drug, for something to take her mind away from life, to make the world bearable. “I just need it, like without it I can’t handle all this. I’m gonna pop somebody,” she said.

Though Beauty uses K2, she actively dissuades those around her from dabbling in it. When a friend spoke of interest in trying the drug, she responded: “If you’re serious about doing that, I’m gonna be with you and make sure you’re safe. You’re gonna be inside and you’re not gonna do it by yourself, you hear me? But I don’t want you to do it.”

She says this, expression firm, as she smokes her joint, disregarding laughter of others milling the scene along the fence. It’s not a joke to her.

She knows she will probably have more seizures. When she does, she goes into the ICU, where she lies sedated on a narrow bed partitioned from ward chaos by a higher form of shower curtain; nurses pass otherwise, distracted, attending to others. There is little they can do for her: she is no longer seizing or in imminent danger that they know of. Here, she waits to be transferred to an inpatient floor to be put on an IV and monitored for a day before release.

In the hospital, doctors cannot tell her what is happening, only tell her to stay away from K2. They cannot convey a tidy explanation, because no one knows quite what to say about a drug that’s constantly mutating, one whose effects can’t be pinned down.

“I’m gonna calm it down. I’m gonna calm it down soon, for real,” Beauty said. She says it every few months, every time she’s hospitalized, when she’s forced to notice how bad her need has become.

Cassie Rodenberg is a writer exploring poverty and deviance. She has written about science for Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and Discovery Channel

The rise of K2: the drug is legal, dangerous – and can’t be stopped

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder