On 9 December 1952 the Great Smog officially ended – for five days a thick layer of air pollution, mostly caused by coal fires, had covered London and caused the deaths of thousands of residents. 64 years later the London Mayor has committed £875 million to tackle the problem. This week the Royal Society of Biology hosted an event on air pollution and health (#greyskythinking) and the Royal Society of Chemistry will run their annual Air Pollution conference next week. After two centuries of fatal London fogs, what have we learnt?

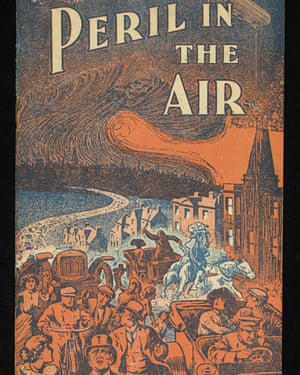

Fogs were relatively common in London in the 1700s, but by the early 1800s these had become deadly, as the smoke and fumes from industrialisation and urban growth were trapped by calm, still air. It was not just the pollution that was a threat to life and health, but also the traffic, and newspapers were full of tragic stories of accidents: in the 1837 December fog the Times reported that “an aged female named Jane Wilson” was “knocked down by a cart and severely injured” and Chelsea resident Mr Phillips was thrown out of his chaise into the road where a “cart passed over his right thigh, and fractured it dreadfully”. Animals suffered too – in 1873 the annual cattle show at Smithfield market was ruined by a December fog that left the “fat cattle…panting and coughing”, and many of the animals collapsed and died.

The Victorians are famous for their public health activity – ambitious sewer schemes, the introduction of Medical Officers of Health, and vaccination programmes – so why did they struggle, as we do, to deal with deadly air pollution?

If it’s everyone’s fault, it’s no one’s fault

One problem lay in the fact that the smogs had many causes. Heavy industry was one source, but so too were the railways and steamer-boats,and particularly domestic coal-burning fires. Various societies were formed to campaign for what was often called ‘smoke abatement’, but they met with resistance. At a meeting of the ‘Noxious Vapours Abatement Association’ in Manchester, a representative from the Health Committee of the Salford Corporation (like a modern city council) won applause from a working class audience when he objected to smoke abatement because

“he would be sorry to see a persecution commenced against the manufacturers, for if they were driven from the borough, where would the bread of the working man come from?”

If ‘big business’ wasn’t going to reform, why should individuals? Smoke abatement campaigners seem to have thought that education was all that was needed: in 1881 the Smoke Abatement Committee opened a smoke-prevention technology exhibition in London which attracted an extraordinary 116,000 visitors in just a few months; all the installations were independently tested to make sure that the manufacturers’ claims were accurate. Yet this did not lead to a mass take-up of smoke-reducing technology, and an attempt to force changes by passing a law regulating domestic smoke failed in 1884.

Some industries had been regulated by the Smoke Nuisance Abatement (Metropolis) Act of 1853, but only in London, and this excluded some factories such as glass works and potteries. Rather oddly, a lot of the discussion about this Act focused not on the health risks of smoke, but on the expense of laundry caused by the dirty air of London (estimated as high as £2 million) – as one member of the House of Lords suggested: “The smoke so affected the clothing of the working classes that it was computed every mechanic paid at least five times the amount of the original cost of his shirt for the number of washings rendered necessary.”

Who pays the price?

Even if it saved on washing bills, there was a genuine fear that over-regulation might lead to job losses. Worse, the Victorians were also concerned that reforming domestic fireplaces would actually make people sicker, rather than healthier. Although open fire places were serious sources of coal smoke pollution, they had one advantage over more efficient systems: they created draughts. Through most of the nineteenth century medical professionals thought that disease was spread by ‘miasmas’, clouds of harmful matter. One way to tackle the danger of miasma was to ensure air did not become ‘stagnant’, and open fireplaces helped to create a ‘healthy’ circulation of air.

While the larger, airier homes of the middle and upper classes could be ventilated in other ways, investigations into the slums and basement dwellings of the poor suggested that open fires were vital. Of course, this could be solved with serious slum clearances and massive investment in homes for the poor, but it proved hard to justify that expense on the grounds that it would prevent air pollution. In any case, reformers worried, people were ‘sentimentally attached’ to their open fires, and resisted technological change.

Suggestions to solve the smoke problem remained small scale: taxes on new stoves or fireplaces, restrictions on certain manufacturing plants, the formation of small local societies to help people buy efficient stoves ‘by instalments’, and so on. But one problem not tackled was the rather obvious one: pollution travels. Responsibility for enforcing anti-pollution and anti-smoke laws rested, by the late 19th century, with local governments and the London County Council, so if pollution was blowing in from a factory in an uncooperative neighbouring jurisdiction, there was nothing councils could do to enforce the limited rules that existed. In 1914 central government was finally persuaded to set up a committee to reconsider the legislation about pollution, but its work was interrupted by the outbreak of war.

It was not until 1956 that a Select Committee’s recommendations, pushed by backbenchers against a sceptical Conservative government, led to the passing of the 1956 Clean Air Act, a direct response to the smog of 1952. For the first time, this Act regulated domestic fireplaces as well as industrial furnaces, and created smoke control areas where only smokeless fuels could be burnt.

Although a milestone in public health, just 60 years later Londoners are dying, again, from polluted air. Although the London Mayor has announced that funding for this problem will be doubled the challenges remain essentially the same faced by the Smoke Abatement Leagues in the 1800s: the causes are complex, some pollution is (thought to be) linked to economic growth and jobs, there are social reasons why people resist changes (especially if they require personal sacrifices, such as giving up car or air travel) and the miasma of pollution still travels across regional and national boundaries. Do we have any new solutions?

Over 200 years of deadly London air: smogs, fogs, and pea soupers | Vanessa Heggie

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder