In the Victorian summer, before motor transport, British cities were thick with houseflies. They bred on horse-dung heaps, dark swarms of them. Without fridges, or cling-film, to keep them at bay, flies flew from open privies into milk jugs and bowls of sugar, and clustered on fruit, bread and raw meat. Some people hung up sticky flypaper in kitchens to trap them, and others had “safes” made from wire gauze to protect food, but not everyone bothered.In 1903, a medical officer for Brighton observed a poor home where the flies had to be “picked out of the half-empty can of condensed milk”.In many kitchens, the presence of flies was so familiar as to seem harmless. But these insects were killers.

It was only in the early 1900s that British doctors realised that the housefly could carry disease on its bristly legs: flies were a major transmitter of both typhoid and summer-sickness, causing thousands of deaths each year. After the hot summer of 1911, there was also rising public panic about the high levels of infant mortality from diarrhoea. Medical officers decided that they needed to change the way the British public felt about flies. As one expert in preventive medicine put it in 1914, people needed to know that the fly was “a loathsome, dangerous pest”.

The problem was that the general population was simply not disgusted enough by flies. People tolerated them because they had no way of conceiving the harm they could do.

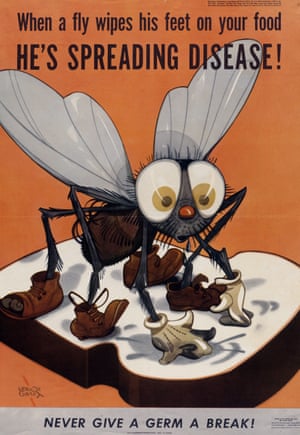

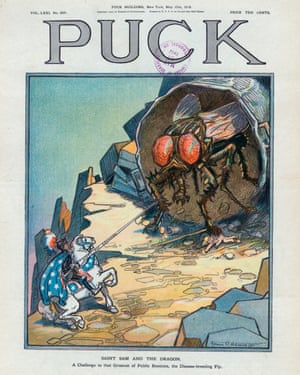

There followed – from 1911 onwards – a vigorous anti-fly campaign of posters and community outreach, spearheaded by the Natural History Museum. The campaign was explicitly based not just on information but on the “creation of disgust”, as historian Anne Hardy, of the London School of Tropical Medicine, describes it. The anti-fly posters were fearlessly graphic. Some of the images – displayed in schools, hospitals, municipal halls – depicted flies on bowls of milk, on pools of vomit and on rubbish heaps. But the main theme, Hardy noted, was very detailed images of “flies sitting on shit”. So much for Edwardian propriety. The anti-fly campaign – reinforced by medical officers spreading the message to mothers and children in local communities – was designed to trigger feelings of revulsion. It worked: the campaign definitely changed people’s feeling about flies. It didn’t stop infant diarrhoea overnight, but it was one of the reasons that the death rate from diarrhoea fell steadily from 1913 onwards. The anti-fly campaign saved lives.

You can’t mistake the look of disgust: a wrinkling of the nose and slight protrusion of the lips, as if trying to expel an offensive odour, as Charles Darwin observed in 1872. This visceral emotion is one of the main drivers of human behaviour. We recoil from the rotten, the stinking or anything that reminds us too strongly of death. This being so, disgust seems an obvious emotion to enlist in the cause of public health. In 2004, the British Heart Foundation triggered a big rise in calls to its helplines after showing ads featuring repulsive images of cigarettes oozing with fat. In 2012, Australia went even further, introducing cigarette packets with gruesome photos of gangrenous toes and diseased lungs, which seem to have achieved the objectives of making smokers enjoy smoking less and become more likely to quit.

But disgust has seldom been called on to improve diets or hygiene. In the modern world, individuals are often disgusted by things that might do us good – such as liver and leftovers – and not disgusted by things – such as unwashed hands and sugary drinks – that do us harm. Disgust can still be a matter of life and death but it doesn’t seem to be working for us any more.

Photograph: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

This is a puzzle, given that many scientists now believe that the original function of disgust for humans was simply to keep us healthy. After years of studying hygiene behaviour in Asia, Africa and Europe, Professor Valerie Curtis, the director of the Hygiene Centre at the London School of Tropical Medicine, noticed a common thread to the things that people found revolting: “The odorous, the grubby, the leftover, the discarded.” Everywhere, the single thing most likely to trigger disgust was faeces. After that came – among other things – animals, insects, dirt, pus, snot, hair and blood. It struck Curtis that all of these are carriers of parasites or disease – or proxies for those carriers. Disgust, Curtis decided, must have been an adaptive mechanism to prevent humans from coming in contact with infection. As she argued in her short book Don’t Look, Don’t Touch, Don’t Eat: The Science Behind Revulsion, humans have evolved to be “disgustable”.

“Emotions are the key to changing people’s behaviour,” Curtis told me one afternoon, speaking from her office in Bloomsbury. “It’s not education that will do it. It’s not knowledge. Disgust is the obvious emotion you can call on in public health. If you want a child to stop touching poo, you don’t talk to them, you just pull a face.”

The creation of disgust around flies, according to Hardy, was a major achievement of the early 20th century. The question is why disgust is not called upon more to solve modern health problems. Take handwashing. A 2010 study found that, when swabbed, 28% of UK commuters had faecal bacteria on their hands. Washing with soap and water after going to the toilet and before eating is the single best way to reduce rates of gastrointestinal illness, yet estimates by the Lancet in 2003 suggested that fewer than one in five people in the world actually do it. Many in the developing world have no access to soap and running water – or toilets, come to that – but in cities such as London, where all the necessaries are abundant, hand-washing rates are still very low. This has consequences. There are more than a million cases of food poisoning a year in Britain. When we get sick, we are likely to blame it on someone else’s cooking: a dodgy curry, an iffy prawn. Yet around a third of cases of gastrointestinal illness could be prevented through observing basic hand hygiene.

Anne Hardy sometimes watches people in department store loos – the kind equipped with deliciously scented hand wash and jet dryers. She is startled by the number of women who exit a cubicle, look in the mirror, then rush straight out. “Maybe they don’t make the connection. They don’t think there are germs on the door and on the sink.”

“Have you washed your hands?” I bark at my children every night before we eat. Each time, they react with fresh consternation, as if I am weird. I never bothered so much with hand hygiene myself, until a few years ago, when researching an article on food poisoning. What I discovered made me queasy at the sight of multiple grubby hands passing round a single block of parmesan cheese. For me, it now feels uncomfortable not washing my hands before eating. Growing up, though, handwashing happened, if at all, after a meal. My mother worried more about stickiness than germs.

The British generally have very low levels of disgust about both unwashed hands and poor kitchen hygiene. There’s a robust pride in eating a slice of toast that’s only been on the floor five seconds and not being one of those fussy people who carries antibacterial hand gel (and besides, a bit of dirt is good for the immune system, isn’t it?). Obviously, you wouldn’t want to become compulsive about handwashing, but most of the British population is very far from this. Food poisoning – most of it caused by faecal bacteria from unwashed hands – costs the UK economy nearly £1.5bn a year. A 2003 study found that Britons suffer to a greater extent from traveller’s diarrhoea than Americans, Australians or Europeans.

One evening recently, Hardy, who is half-Danish, met friends for a meal after work and noticed that even though most of them had been on public transport,almost everyone sat down and started crumbling bread straight away. Some people make a point of washing their hands after going on public transport, but such habits are still exceptional. If you spread germs by spitting in the street, everyone knows about it. But the act of non-handwashing, Hardy notes, is “quickly and discreetly achieved”.

Rates of handwashing in Britain don’t seem to have improved since the second world war, when Lord Woolton urged the general public that handwashing after using the toilet would reduce food poisoning. There are notices, particularly in restaurant toilets, that say “Now Wash Your Hands”, but Hardy is convinced that nobody pays any attention to them. The majority of humans – in Britain and elsewhere – are not disgusted by their own fingers, no matter where they have been. We think about them as the late Victorians thought about flies: hardly at all. We spend a fortune on deodorant and mouthwash to create an aura of “freshness”, but neglect the basic soap and water that might prevent us getting sick quite so often. But would the situation change if governments were bold enough to create graphic public health campaigns centred on disgust? And if they did, would we find them too offensive to look at?

Our ancestors were the fastidious ones, on Valerie Curtis’s reading: the survivors in any given community who declined to eat rotting flesh, who shunned neighbours whose faces were covered in lesions and who were wary of unfamiliar dishes. Our ideas of disgusting food are very culturally specific. “Why will the Chinese eat rotten eggs, the Swiss rotten milk, and the Ugandans grasshoppers?” she asks. Curtis’s answer is that all foods are “potentially disgusting, but we make exceptions for what is familiar”. If we grow up seeing others crunching on grasshoppers, we feel reassured that they are not something disease-ridden. “In every society infants accept what their mothers feed them … but novel foods are treated with suspicion, to be rejected, sniffed at, or tasted only in small bites.”

If this is true, why are we not more disgusted by foods that cause us harm? From January to March this year, analysis showed that about 79% of the chicken for sale in Britain was contaminated with campylobacter, a bacteria responsible for an estimated 280,000 UK cases a year of a particularly vile form of food poisoning, and approximately 100 deaths. Yet somehow, most of the population remains undisgusted by mass-produced chicken. People look at it and see nothing but “white meat”: something safe and protein-rich, served up in neat portions, in an apparently sterile plastic tray. As Curtis comments, “they take away the feathers and the shit and make it look like a pure thing”. Your senses do not tell you that this contains pathogens. “We need to listen to some kinds of disgust and not others,” Curtis says, but in the modern world, it is increasingly hard for our brains to learn the difference.

For years, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) has been trying to raise British awareness of campylobacter, and to persuade the public to cook chicken scrupulously and wash chopping boards and hands in hot water after touching raw poultry. For years, consumers have been resolutely ignoring these earnest pleas. But perhaps the anti-campylobacter message has been far too safe and rational. It doesn’t push our disgust button. Just last year, the FSA ran a “Chicken Challenge”, urging the public to “be careful” and make an online pledge to “help cut campylobacter food poisoning in half” by the end of the year – a meek and dull approach that did little to broadcast the true dangers. The hope was to change the way the whole country thought about cooking chicken but by August 2015, just six local councils and 3,521 individuals had signed up.

Despite all the resources poured into the “Chicken Challenge” campaign, the FSA was not brave enough to use disgust to make people think twice about eating poorly cooked chicken. A hard-hitting campaign linking explicit imagery of bloody diarrhoea with undercooked barbecued drumsticks might have done the job. “But the food industry would never let you do it,” says Curtis. There are a lot of vested interests in the modern world, working to keep our disgust levels for certain things low. Supermarkets sell meat adorned with bucolic cows and sheep from prettily named farms, to stop us from thinking of the slaughterhouse. Adverts for female sanitary products show us innocuous blue liquid, nothing that threatens to make us think of menstrual blood.

Disgust is an alarm system that we have become very good at switching off. It seems there would be no way for health campaigners to switch disgust back on again without upsetting a lot of people.

In 2005, Jamie Oliver showed a classroom of schoolchildren how to manufacture chicken nuggets using grisly pink mechanically recovered meat, chicken skin, fat and additives, on an episode of Jamie’s School Dinners. In another memorable scene from the programme, all of the junk food eaten by a single class of children at one school in a single day was piled up in a giant sugary, fatty refuse heap. Like the graphic anti-fly posters of the early 20th century, this disgusting imagery had an immediate, beneficial impact on public attitudes. Some criticised Oliver at the time for being so prescriptive, but his deliberate deployment of disgust was one of the factors leading to the adoption of more rigorous standards for UK school meals in 2006.

If the Chicken Challenge’s mild exhortation to “be careful” didn’t work, could food-related disgust be use more widely to help us adopt more healthy diets? Paul Rozin, an American psychologist, believes that it can. On a bright Saturday morning this July, Rozin told a rapt audience at the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery his solution to rising obesity: make fast food restaurants serve pre-chewed food. He was joking, but not entirely. Rozin’s point is that provoking nausea is a much quicker and more effective way to stop someone eating something than simply telling them it is not healthy. One of Rozin’s many experiments found that you can kill a person’s appetite for sweets – temporarily, at least – if you offer them a box of chocolates with a small bite taken out of each one. “These don’t sell!” says Rozin.

Rozin, who is 80, has a gravelly voice full of wry humour and seems very comfortable in his own skin (when on Skype, he does not always wear a top, as I discovered one morning when he spoke to me bare-chested, propped up against a red pillow in bed, during a trip to Barcelona). For four decades, he has been trying to unravel the meaning of disgust. No one since Darwin has added so much to our knowledge of this paradoxical emotion. Rozin was the dominant scholar in disgust studies before the evolutionary biologists entered the field, and he doesn’t buy Valerie Curtis’s theory that disgust was originally an adaptation to keep us safe from pathogens. To Rozin, this emotion is something far messier and more complex than basic microbe-avoidance.

“If people were so predisposed [to avoid pathogens] you’d think it would be easy to wash their hands after they defecate,” he says. “But they don’t.” On his reading, disgust is basically about food, rather than pathogens. Disgust, for Rozin, is about avoiding more than simply disease. A fully developed sense of disgust does not appear until somewhere between the ages of two and five. In the 1980s, he found that very young children were often happy to drink a glass of apple juice which had a dead cockroach dropped in it and then removed. For most adults, by contrast, the cockroach rendered the juice undrinkable because it left them feeling that the juice was permanently contaminated. It didn’t matter how much Rozin reassured them that the cockroach was sterile and safe. Most people didn’t even want to drink fresh juice from the same glass when the “roached juice” was poured away. The glass itself seemed to be crawling.

It is Rozin’s theory that disgust is, at root, a response to situations that remind us how close we are to being animals. “Almost all disgusting food is of animal origin.” To some children, unfamiliar green vegetables may provoke distaste – the fear that something will taste bad – but disgust is something more. We don’t care whether rat meat tastes bad (though I suspect it would), we just don’t want it in our mouth. “A basic feature of disgusting foods,” Rozin has said, “is that if they contact an otherwise desirable food, they render it inedible.” A key element of disgust is contagion.

Where Rozin agrees with Curtis, however, is that generating useful forms of disgust would be a potent way to change unhealthy behaviour.

There is a huge amount at stake here, given that poor diets now cause more death and disease in the world than tobacco (10% as against 6.3% as of 2010). Instead of telling us that sugar-sweetened drinks are delicious treats that we must try very hard to resist, what would happen if governments tried to make us see them – like Edwardian houseflies – as “loathsome, dangerous pests”? “I think these drinks are disgusting,” says Curtis. Selling them to children is “child abuse”. In 2009, New York City launched a deliberately nauseating ad campaign depicting globs of human fat pouring from a cola bottle. “Are you pouring on the pounds?” was the tagline. Consumption of sweetened fizzy drinks dropped by 12% in the city after the campaign.

During my teenage years, the smell of fast food was like catnip. I knew it was bad for me, but that didn’t stop me wanting it. Over time, my tastes changed and I started to find that burger-smell revolting: that sweetish meaty stench, the oiliness of the fries. It is no hardship to go without something when it turns your stomach.

Recruiting this strange, dark emotion to the cause of public health is not without problems, though. The danger – and this may explain why modern policy-makers are often reluctant to dabble with disgust – is hitting the wrong target. It’s one thing to say that fattening foods and drinks are disgusting; quite another to attach disgust to the people who consume them. Many obese people already suffer from a debilitating sense of self-disgust and anything adding to the stigma would be damaging and counter-productive.

When turned into a moral emotion, disgust can assume an ugly face. It has been demonstrated that some people have a disgust response not just to earthworms and spoiled milk but to those who are sick, elderly or disabled. Curtis has seen in Africa and Asia how quickly certain groups of people can be treated as dirty or untouchable. “We want people to wash their hands but we don’t want to stigmatise those who have no access to a toilet,” she says.

Curtis was once involved in trying to develop a pro-breastfeeding campaign in the developing world. The aim was to make mothers feel disgusted about formula milk, whose use contributes to infant mortality in communities without access to clean water. “They should be disgusted,” Curtis says. “We know that there are high concentrations of faecal bacteria in the milk,” which comes from the water used to dissolve the milk powder. “But some mothers have to bottle-feed and we don’t want to make them feel disgusting.”

No one wants to be made to feel disgusting, which is perhaps why there is such reluctance to call on disgust to change people’s behaviour. But Curtis argues that, if it produces the desired change in people’s behaviour, we should have no qualms about provoking powerful emotion. In Britain, the consequences of unwashed hands may be a nasty stomach bug. In the developing world, it is often death. It has been estimated that handwashing with soap, if it became a universal habit, could save 600,000 lives a year.

We retain faith in the power of facts to change behaviour, but what motivates us above all else is emotion

One of the reasons people are not disgusted by unwashed hands is that they can’t see the germs. “Disgust only works when it’s salient,” says Paul Rozin, meaning that you have to notice something before you can be disgusted by it. Curtis and colleagues worked with a Ghanaian advertising agency to bring home the idea that faeces is still present on the hands even when you don’t see it. They designed a TV commercial showing a nice-looking young mother leaving a toilet and preparing food for her kids, using her hands to knead dough. The film showed her with a smear of purple on her hands from the toilet.In the film, the purple passed from the mother’s hands to the food to the child’s mouth. When Curtis showed the first cut of the ad to mothers in Accra, she heard a sharp intake of breath and saw horror on their faces as they realised that faeces was being fed to children. “It didn’t need words,” Curtis says.

As a society, we retain faith in the power of facts to change behaviour, despite ample evidence that what motivates us above all else is emotion. Disgust will often get the job done far quicker than information. When devising the handwashing advert in Ghana, Curtis knew that she simply had to make mothers see that they were “feeding their children poo”. It took her British team of researchers a long time to come up with purple as the colour the audience would find most creepy on the mother’s hands. The ad was extraordinarily effective. It was shown on Ghana’s three national TV channels for a year. A nationwide survey suggested that eight to 10 months into the campaign, handwashing with soap had gone up by 41% before eating and 13% after using the toilet.

In theory, rich countries could also try to sicken people into more hygienic behaviour. In 2007, researchers in Sydney placed some graphic posters in two washrooms, depicting a long bread roll filled with faeces. These revolting images were placed above the sinks and in the cubicles. Over a six-week period, the washrooms decorated with excrement sandwiches got through more soap and paper towels than a couple of control washrooms featuring posters showing clean hands and a bland informative message about disease prevention.

There are downsides, however, to making people feel more disgusted than they already do. Shocking images on cigarette packets are one thing, because no one has to smoke. But everyone uses the toilet, and forcing people who already wash their hands to look at sickening pictures seems unfair. As it is, we are already far too disgusted by many things. There is such a thing as too much disgust, when it comes to health.

When home cooks neglect to wash their hands after handling raw chicken heaving with campylobacter, the problem is that they are not disgusted enough. But there are cases where we are too disgusted to do things that might have public health benefits. Drinking recycled wastewater is an example. With climate change and increasing scarcity, finding new sources of drinkable water is a pressing concern. But that might be the easy part. Persuading people to drink it is another matter.

In 2008, in drought-ridden Orange County, California, engineers set up a plant converting sewage water into drinking water. The water passed through a number of filters and purifiers until it was perfectly clean and pathogen-free. But local officials found that the “yuck factor” from residents was too great to put this water in taps, so most of it was pumped into the ground, to fill up aquifers. When surveyed, much of the population said that drinking the recycled water directly would be like sipping straight from the toilet. As one of Rozin’s colleagues, Carol Nemeroff, asks: “How do you get the cognitive sewage out, after the actual sewage is gone?”

Related: How insects could feed the world | Emily Anthes

The most effective way to make people get over their disgust about wastewater, Rozin says, would be to put it in the taps without telling anyone, wait a few months and then say: “Guess what? You’ve been drinking sewage water!” The catch, he sees, is that it wouldn’t be considered ethical to lie to people in this way. Rozin would like California to emulate Singapore, where people are invited to go on tours of the plants that recycle the water as a way of reassuring them how trustworthy the process is. At the end of the tour, each visitor gets a free bottle of the water, which looks like mineral water.

The main way to overcome disgust is through repeated positive exposure.

It’s generally harder to eliminate disgust than it is to acquire it in the first place – Curtis calls it a “sticky” emotion – but our sense of what is disgusting is far from fixed. A generation ago, the concept of raw fish seemed alien and slightly repugnant to many in the west. Now, sushi is the 10th favourite food among Americans (according to Globescan 2011) and sold as casually as sandwiches in British supermarkets.

In fact, changing the foods that disgust us could be a crucial element in feeding rising populations. Canadian food writer Jennifer McLagan – author of Odd Bits, a celebration of offal – is on a mission to try to persuade cooks to be less disgusted by blood, which she regards as a sustainable form of animal protein. Because of the way meat is produced, the world, McLagan notes, is “awash” with this excellent source of protein and iron, but most of it gets wasted. Some is dumped into rivers and lakes, which causes pollution, increasing the nitrogen in the water. The key to avoiding this pollution – and getting some cheap nutrients into the bargain – would be eliminating our disgust for cooking with blood. McLagan finds pig’s blood a marvellous substitute for eggs, with half the calories. In her Toronto kitchen, she whips fresh blood into a stable pink foam, which she uses for anything from rich brownies to dark brown blood meringues. I tried some of both. They tasted good, with a slight metallic tang. But most western consumers find the very idea of handling blood too horrifying even to contemplate.

In harsh economic times, people may find themselves forced to swallow their disgust for certain foods. Consider insects. Environmentalists are now touting insects as one solution to the problem of finding a more sustainable source of animal protein. Me? I think eating insects is a great idea, so long as someone else does the eating. But Rozin has found that many insect-haters would get over their disgust, if only they could be persuaded to try them enough times – a similar reaction to that which many westerners have to sushi.

Last year, Rozin and a colleague called Matt Ruby interviewed 400 people from India and the United States about how they felt about eating insects. Women, they found, were less willing than men to try insects, particularly in the US. Indians worried that eating insects was wrong, while Americans worried they were unhygienic. But most of those questioned said they would try insects if they were ground into flour and used to fortify a cookie or a dosa. Only 25 to 30% of those questioned still held out against eating insects even in this mild and unobtrusive form. The people most open to eating insects were thrill-seekers who described themselves as enjoying adventurous flavours.

Disgust may be a universal emotion, but we vary hugely in how strongly we feel it, and what our triggers are. Each of us fall somewhere on what Rozin calls the “disgust sensitivity scale”, a system he devised with another psychologist, Jonathan Haidt. You get an overall disgust rating based on how bothered you are by a range of triggers. These include:

You see someone put ketchup on vanilla ice cream, and eat it.

You see maggots on a piece of meat in an outdoor garbage pail.

You see someone accidentally stick a fishing hook through his finger.

You are about to drink a glass of milk when you smell that it is spoiled.

You are walking barefoot on concrete and you step on an earthworm.

For those who are lower down on this scale, it should be fairly easy to reduce or eliminate disgust for something like eating blood or insects – particularly with the right incentives. Rozin has found that a financial reward will often make someone swallow their disgust for certain things. If insects were cheap, familiar, and marketed in appetising ways, many people would gradually shed their disgust and greet them with pleasure. Or we could just wait until a crisis some time in the future when food is scarce and we become grateful for all the crickets and pig’s blood we can get.

The real puzzle is why most of us are disgusted by insects and offal, and not by other meat – mass-produced bacon, say – even though we know it is produced in conditions of cruelty and squalor. If governments were really determined to get rich populations to eat less meat – something that every expert on sustainable diets says needs to happen, and urgently – they would send schoolchildren to visit slaughterhouses instead of farms. It should be possible to generate mass disgust about unsustainable levels of meat eating, until a kebab seems as unappetising as a pile of crickets. The question is whether, as a society, we would ever want to. Like the rest of us, most politicians seem happy to carry on eating bacon sandwiches and pretending nothing is wrong.

We are now so “disgustable” that we have become squeamish about disgust itself. We live in a sanitised environment that hides from us the extent to which we still live with pathogens and other dangers to our health. Maybe the real reason we don’t use disgust more in the cause of public health – despite all the evidence that it would work – is simply because it grosses us out even to think about it. Valerie Curtis was once booked to speak at a conference on “self-neglect”, about people who become isolated and abused, owing to a lack of basic hygiene. There was so little interest that the conference was cancelled. Even if it might help us to lead healthier lives, we would rather leave the whole topic of disgust in a dark place under a rock, with all the other creepy-crawlies.

Bee Wilson is the author of First Bite: How We Learn to Eat (Fourth Estate)

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.

This article will make you want to wash your hands | Bee Wilson

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder