From his high-rise office building in Hanoi, Tran Dung can barely see his city’s skyline behind the thick layer of smog. Before leaving work, the 25-year-old executive assistant checks the pollution reading on his AirVisual app, which provides real-time measurements of PM2.5 – the tiny particles found in smog that can damage your throat and lungs.

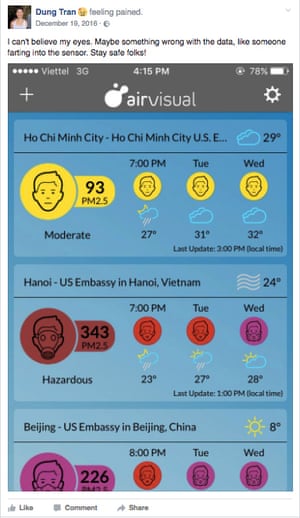

Hanoi’s PM2.5 levels typically range from 100 to 200 micrograms per cubic metre – regularly within the globally acknowledged “unhealthy” category. But on 19 December last year, they hit “hazardous levels” at 343μg/m3, which was higher than Beijing.

Shocked by this reading, Dung shared a screenshot with his friends on Facebook, writing: “I can’t believe my eyes. Stay safe folks!”

He’s aware of the limitations of air quality data, which can vary between different parts of the city, but apps like this are the best tools he has.

According to the independent data measurement site AQIVN, there were at least 15 days in 2016 where average PM2.5 levels in Hanoi were “hazardous”, at 300μg/m3 or higher. On 5 October last year Hanoi had the worst air pollution among major cities across the world, generating widespread outcry over public health.

Dinh Nam, a lecturer at the Vietnam National University in Hanoi, does not need an app to tell him that the air quality is bad. “Every day I motorbike over 8km to get to work,” he says. “I can see the smog sitting on my clothing and my skin every night.”

Nam moved to Duong Noi, a new urban area far from the city centre, four years ago hoping to escape the pollution and traffic that the dense centre brings. However, as Hanoi continues its aggressive expansion policy, smog has caught up to his family; the area, which is close to the Yen Nghia industrial zone, has seen a simultaneous boom in high-rise construction and industrial development. The fumes from motorbike exhausts, construction and industry have made breathing a source of fear for Nam’s family. Aside from flimsy face masks, he has no other means to protect himself and his children.

When Hanoi joined a growing group of global cities to launch its first bus rapid transit route on the last day of 2016, it should have been good news for Nam. It was hoped that the new BRT would take some of the 5 million motorbikes and scooters off the roads and reduce congestion and pollution in the city.

Despite now having a BRT stop 500 metres from his house, Dinh Nam remains skeptical of the $ 53.6m development, funded by loans from the World Bank. “When the project was initiated 10 years ago, this area was much less congested than it is now. Now, the roads are so crowded it can’t be effective,” he says.

Dinh Nam’s skepticism represents the backlash BRT has faced in Vietnamese media since its launch. Many are angry that the BRT’s exclusive lane takes up almost half of some roads, exacerbating congestion for other motorbikes and cars. Others have predicted that BRT would never achieve the promise to cut travel time in half, given the challenges faced by keeping the lane free. But long before the launch, questions were already raised on whether the loan would be worth it.

The media’s declaration that BRT was dead upon arrival indicates declining trust towards the government’s handling of environmental and infrastructural challenges.

An ongoing struggle

Despite the brouhaha, many have already incorporated BRT into their daily routine. The 5pm bus towards Kim Ma on Thursday had all of its seats occupied and a handful of people standing. A dozen more gathered behind the shiny automated doors at the Giang Vo station, waiting to get in.

An official report from Hanoi’s transport document concluded that BRT passengers had risen over 62% in the first 12 days of its launch, averaging 41 passengers per trip. However, this means BRT is still operating under capacity, as can hold up to 90. Furthermore, it seems most passengers are students or retirees who are probably already accustomed to using public transport.

Given the low adoption, it is still too early to say whether BRT will have a positive impact on Hanoi’s air quality. The average monthly PM2.5 reading for January 2017, calculated using historical data collected at the US embassy directly on the BRT route, even shows an uptick in air pollution compared with December. However, it could be to do with the changing traffic patterns during the Vietnamese new year at the end of January.

Dr Hoang Xuan Co, an expert at the Research Centre for Environmental Monitoring and Modelling in Hanoi, says: “In theory, implementing BRT should improve air quality by reducing the amount of private transportation. However, there are ongoing challenges with implementing BRT: the infrastructure in Vietnam is still incomplete [for example, there are no hard dividers between the BRT lane and the regular street], and people’s transportation habits are unchanged. It has been almost one month, the people have yet to see BRT really impacting air quality.”

Hanoi currently has a declining 1.3 million daily bus users, a small number in comparison to the millions of motorbike drivers. The city also has a growing appetite for cars. It is worrying that many motorbike drivers who live within the BRT route and are highly critical of its construction say they have not even considered trying it.

Motorbike culture has engrained a need for flexibility and control in many Hanoians – some do not even get off their bikes when picking up meat and produce at wet markets. Dinh Nam is afraid that transitioning to BRT would reduce his flexibility in taking care of his family. “BRT is not for me because I sometimes have to pick up my kids,” he says.

Nguyen Dung, meanwhile, avoids the BRT as she does not want to walk to and from the bus stop.

Vu Anh Tuan, director of the Vietnamese-German Transport Research Centre, believes BRT faces the challenge of promoting public transport in a motorbike and car culture.

“BRT is a wise investment because it can complement the planned metro system to form routes throughout the city, while keeping costs low. Its impact needs to be assessed by what the entire public transit network can do in the long term,” he writes in a passionate Facebook post.

“The media … will cause people to develop false perceptions about public transportation, especially BRT.”

It seems Hanoi’s new BRT system will only be able to make an impact on both reducing congestion and air quality if people are willing to change their habits.

Guardian Cities is dedicating a week to exploring one of the worst preventable causes of death around the world: air pollution. Explore our coverage here and follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion

Hope for Hanoi? New bus system could cut pollution … if enough people use it

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder