Dr Nadia Masood’s public involvement in the junior doctors’ dispute began in a layby somewhere in north-east London on 11 January. “I was driving to Essex to see my mum, who was in hospital with sepsis after having chemotherapy for breast cancer. I was listening to LBC and James O’Brien was talking about the first junior doctors’ strike, which was due the next day,” she recalls. “I pulled over, phoned in and ended up on air, trying to explain to listeners why we were going on strike. I was feeling very emotional both because of my mum and because of the strike.”

It was unusual behaviour for the 35-year-old anaesthetic registrar. “I’m from a completely apolitical background. I didn’t have a political bone in my body until the health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, decided to impose an unfair and unjust contract on 54,000 junior doctors,” Masood says. “At first I saw the contract as an ethical, not political, issue. It wasn’t right to impose a contract on a workforce who give up their entire lives and pour blood, sweat and tears into their jobs and have no choice but to work under the conditions the NHS gives us, because that’s the only way we can become consultants, which is our goal. I was shocked Jeremy Hunt had the balls to do it.”

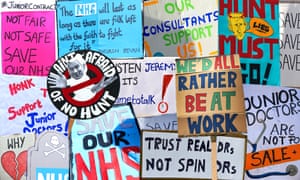

The next day brought the first of what would be eight strikes between January and May. They pitted young medics renowned as workhorses of the NHS against a health secretary regarded with deep suspicion by the medical profession for his disparaging comments about GPs and consultants. Doctors in scrubs on picket duty outside their hospitals vied with Hunt for public sympathy over his insistence that juniors had to work more at weekends to deliver the government’s promised “truly seven-day NHS”.

Striking wasn’t easy for the doctors, who realise the uniqueness of their jobs, which they love, says Masood. On day one she was among the pickets outside Great Ormond Street hospital in London, where she worked at the time. “We were all feeling really bad about refusing to work that day. But parents brought their children outside from the wards to say hello and said they supported us, and our consultant colleagues kept everything running smoothly, which all helped.”

Did junior doctors expect to win? “Yes. That 98% of junior doctors who took part in a ballot organised by the British Medical Association backed strike action to oppose a contract we argued was unfair and unsafe – that made us realise that we all felt the same shock and horror at what Hunt was doing. We all felt justified in our resistance. Maybe I can call this naivety, but I think that the right thing – truth, honour, justice – always prevails in the end,” says Masood.

As walkouts, on-off negotiations and the war of words rolled on, opinion polls showed the medics were winning the battle for hearts and minds, even when they escalated their action to include withdrawal of cover from areas of life-or-death care, such as A&E and maternity units.

“The RMT give the impression that they don’t care [about the impact the rail strikes by their members has on the public], and people think they are being selfish and not handling things right,” Masood says. “But as junior doctors we felt that our motivation was really pure. We were genuinely concerned about the wellbeing of the NHS and genuinely believed that what we were doing was to protect it.

“It wasn’t about money, though Jeremy Hunt portrayed us as money-grabbers by constantly stressing that we’d be getting a pay rise. It was about patient safety and the sustainability of the NHS. Some people thought we were against a seven-day NHS, but most doctors – especially junior doctors – already work seven days a week.

“We spoke about how the NHS was already at breaking point, with too few staff and too little money to do its job properly. But no one took notice of us. But a year on, people like [the NHS England chief executive] Simon Stevens and [the NHS Providers chief executive] Chris Hopson, who distanced themselves from us a year ago, are now saying publicly what we were saying then, that the NHS is struggling with the lack of funding that it has.”

Hunt has insisted hospitals have to be able to roster doctors to work more at weekends to enable the NHS to treat more patients on those days, though precisely what services he wants to be expanded remains unclear. Eight strikes did not force him to backtrack. Masood repeats what junior doctors argued repeatedly throughout the dispute: “There’s not enough doctors at the moment to staff the current service we’re trying to deliver over five days, so why has Jeremy Hunt brought in the new contract when he knows that? It’s madness to stretch a workforce that’s already too small across seven days.”

In May the then chair of the BMA’s junior doctors committee endorsed a revised version of the contract, but members rejected it by 58% to 42%. In August the union threatened a series of five-day walkouts between then and Christmas, but abandoned the plans in the face of huge opposition, both internal and external. Juniors began moving on to the contract in October.

So who won? “They did,” says Masood quietly, her voice trailing away. “The government have won in the short nterm and I’m worried that they will now do the same thing to nurses, consultants – to all NHS staff. But long term I fear that more junior doctors will decide not to train to be NHS consultants and quit, and that more people will be burned out mentally and physically.” She was one of five junior doctors who in September challenged in the high court the legality of Hunt’s decision to impose the contract. That action ended in defeat too.

The dispute has left junior doctors feeling miserable and demoralised, Masood says. She is still so outraged by Hunt’s behaviour that she stepped away from her training last month, even though she is close to becoming a consultant. Her decision means an understaffed NHS is one more medic short. She is taking a career break and now works as a locum in various London hospitals.

“There’s a big need for locums because there are rota gaps in every specialty in every hospital,” she says. “What Jeremy Hunt has done is driven a lot of us out of the NHS, either temporarily – like me – or permanently. He says he values us, but everything he has done has made us feel devalued. I just worry that he will do to other NHS workers what he did to us and if he does, that will kill us as a workforce, and that will kill the NHS, because there will be no one to work in it.”

Junior doctor Nadia Masood: "Hunt"s driven a lot of us out of the NHS"

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder